YES IT IS!

Yet another article to add to the list of reasons for by Colorado. People ask me all the time why things are different here in Boulder. My answer is that every single one of us that lives here knows that we are lucky. We know that we are blessed to get to live in such a gorgeous place. I still look up at the mountains and express my gratitude daily. Yes, I made the choice to live here and I am constantly thankful for the opportunity.

Read more here at The Men's Journal

...

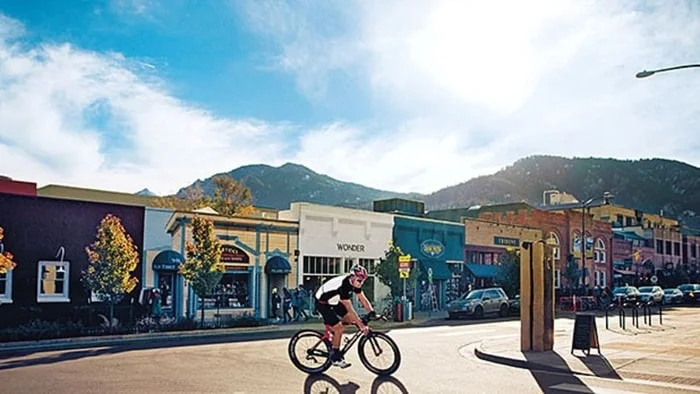

Roaming around Boulder, Colorado, is like stepping into Richard Scarry's busy, busy outdoor town. Everywhere you turn people are doing sporty things.

I didn't realize how busy Boulder was until I visited on a recent Sunday. The town buzzed under a benevolent autumn sun. In the creek next to the public library, a fly fisherman toyed with a brown trout holding in an eddy. Lycra-clad cyclists whizzed by in pairs and trios. Sharing the same path were runners by the dozen. On a nearby lawn, two women moved through Planks and Cobras on orange mats. On Broadway I passed more cyclists and a guy roller-skiing. Colorado Avenue was closed for a bicycle race, so I swung northeast to 47th Street and watched a bearded hipster tow a wooden canoe with his mountain bike. Up Boulder Canyon Drive, young climbers clipped chocks to their racks before red-pointing a sun-warmed route. Everywhere I went, grown men and women paraded about in bike shorts, technical jackets, and yoga pants. The dudes could have stepped out of a Patagonia catalog. The dames looked like models for Title Nine.

As the afternoon waned, I parked and walked across the Chautauqua Lawn, a grassy approach to the dramatic stone slabs of the Flatirons, where the Rocky Mountains end like cleaved bones on a butcher's block. Surrounded by dozens of hikers, I stopped to catch my breath and take in the view. Behind me the Rockies took their final bow. At my feet the Great Plains swept east.

And between them sat Boulder, the healthiest town in America.

The data doesn't lie. In the annual Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index, which measures the nation's physical and mental fitness, Boulder claimed the title of America's healthiest community in two of the index's first five years. In 2015, Gallup-Healthways changed its criteria to include only the nation's 100 largest cities. Boulder, population 105,000, didn't make the cut, so the official winner was Sarasota, Florida, which has an obesity rate of 21.4 percent. Boulder was like, "City, please." Twenty-one percent? Boulder's obesity rate is 12.4.

RELATED: The 10 Best Lazy Rivers in the US

It would be easy to dismiss Boulder's low body mass index as a product of its college population, but the townies here are arguably fitter than the gownies. And its residents' healthiness is just one way that Boulder stands apart. A 2013 study found that it had more startups per capita than any other U.S. metro area — which helps explain why unemployment here is a scant 2.6 percent, just more than half the national average.

That outlier status didn't happen overnight; it emerged from a rich mix of subcultures. Sure, altitude mattered. So did the beautiful natural setting. Money helped. More important, though, was the town's embrace of new ideas and oddball lifestyles. The question now is whether Boulder can maintain that open-minded attitude. Health and fitness were a by-product of Boulder's culture, but now they're becoming one of its main draws — and the town's historic acceptance of the different and the strange may be running into uncomfortable limits.

The first thing you learn about Boulderites is that many of them started out somewhere else. "People typically have success elsewhere and then decide Boulder is where they want to live," said Seth Levine, managing director at Foundry Group, a venture capital firm that's the Kleiner Perkins of Boulder's booming tech community. After making his finance bones in New York in the 1990s, Levine considered a lucrative job in Asia. "I realized that wasn't the life I wanted," he told me. "I was looking for more balance." Balance, in this case, meaning more time to climb rocks and play Ultimate Frisbee.

That's a common Boulder tale. Ari Newman, founder of Filtrbox, is a partner at Techstars, a business incubator that puts startup founders through a three-month accelerator program. Newman moved here from Silicon Valley in 2002. "I knew full well I was making a trade-off," he said. "I was trading economics for overall health and happiness."

Boulder's lifestyle remains a powerful recruiting draw, but now the investment, marketing, and tech talent have reached critical mass. Google will soon expand into a campus for some 1,500 workers at 30th and Pearl. In 2006, advertising guru Alex Bogusky moved Crispin Porter & Bogusky, the hottest shop in the business, to Boulder. Venture capital and tech firms cluster along Walnut Street near the bike shops and Nepalese restaurant. "This used to be a Subaru town," an old friend told me. "Now it's an Audi town." And it's becoming a Tesla town, the Palo Alto of the Rockies.

In Boulder, outdoor activities aren't merely hobbies. They're self-defining.

"At a cocktail party in New York or San Francisco, people ask, 'What do you do?' and they're asking about your job, your social and economic status," Newman said. "People here ask, 'What do you do for fun? Are you a marathoner? Do you ski? Ride?' It's about who you are as a person, not what you do."

It's an alluring mind-set. I once embraced it myself. Ten years ago I moved my family to Boulder for an academic-year fellowship at the University of Colorado. We loved the life so much we didn't want to leave. We'd never been healthier. Our kids played outside. My wife hiked every day and took up telemarking. I snuck out to ski before work. We rented a house built like a national park lodge. Foxes, elk, and wild turkeys wandered through our yard. The sun never seemed to stop shining.

Boulder changes people. Noncommittal joggers move to Boulder and become marathoners. Weekend cyclists become triathletes. Although my own family ultimately left Boulder after two years — drawn back to Seattle by family and lifelong friends — I know plenty of people who can't quit the place. "If you could live anywhere, why wouldn't you live here?" said Hillary Rosner, a Boulder-based science writer. A couple of years ago, Rosner landed a teaching gig at Syracuse University, in New York. She loved the college. The town? Not so much. "The weather's terrible and everyone seemed unhappy," she said. "Other than that, Syracuse was great." After a single semester, a change in her husband's job prompted an about-face to Boulder.

It's like the fisherman's bumper sticker: The worst day freelancing in Boulder is better than tenure in Syracuse.

How does a nirvana like Boulder happen? In this case, you can credit four waves of migrants: the eggheads, the climbers, the hippies, and the runners.

When Colorado doled out the spoils of statehood, Denver got the capitol, Cañon City was given the prison, and Boulder landed the state university, which nurtured a local society that valued freethinkers and new ideas. After early tech businesses like Ball Aerospace and StorageTek set up shop in the area, CU provided a rich, scientific talent pool. Rock climbers, drawn by world-class routes in Eldorado Canyon, started arriving in the 1950s. While the dirtbag lifestyle was being forged in Yosemite — make a little scratch in winter and live frugally to climb all summer — Colorado legend Layton Kor established the practice in Boulder.

The hippies followed in the summer of 1968. They spent a couple of months smoking grass on Chautauqua Lawn and decided to stay. From that gathering emerged the cornerstone figure, Mo Siegel. In 1969, Siegel and some friends harvested herbs in the hills above Boulder and sold them to co-ops in the town's burgeoning natural-foods scene. In the 1970s, he turned that idea into a company called Celestial Seasonings and made a fortune selling herbal teas to America. That attracted other entrepreneurial hippies, like Steve Demos, who started the WhiteWave tofu company here on a $500 loan. Today the $3.6 billion business includes Horizon Organic and Silk soy milk.

Then came the runners or, rather, the runner: the godfather of Boulder's modern fitness culture, Frank Shorter. In 1970, Shorter was a skinny Yale grad who moved to Boulder, elevation 5,400 feet, to test his crazy ideas about training at altitude. Two years later his victory in the 1972 Olympic marathon inspired a wave of runners to move to Boulder. The road cyclists arrived soon after. In 1975, Siegel helped launch the Red Zinger Classic, a bike race named for his bestselling blend, as a way to promote bicycle transportation. Top prize money drew top riders. They came, they raced, they dug the Boulder scene — and they stayed.

The runners and cyclists picked up on the philosophy that the climbers and hippies had laid down in the Sixties: Living for your passion wasn't just OK, it was the right and natural thing to do. They put down roots and built a supportive infrastructure that continued to lure athletes to the town. Shorter brought a generation of runners here. After the Red Zinger years, Olympic medalists Connie Carpenter and Davis Phinney lured other top cyclists. Scott Jurek, the ultramarathoner who recently broke the Appalachian Trail speed record, moved to Boulder in 2010, lured by his friend Anton (Tony) Krupicka, two-time winner of the Leadville Trail 100. "The climbers, the runners, the triathletes, and the world-class yogis — that energy and motivation really draws across the lines of different sports," Jurek told me.

In fact, fitness is culturally valued in Boulder in much the same way wealth is esteemed in New York and political power is revered in Washington, D.C. In Boulder, fitness has become the common currency of success.

Researchers have found that two factors play key roles in a person's level of physical activity: modeling and social support. Modeling is simple. People learn behavioral norms by observing those around them. If you see your neighbors running and riding day after day, then you're more likely to try it yourself. Social support in Boulder means your friends meet for a ride rather than a beer — or, rather, a ride and then a beer.

Wake up early enough and you can see those dynamics at play in the Wednesday Morning Velo, a.k.a. the banker's ride. Slightly past 6 a.m., bicyclists in tight shorts and clickety shoes flock to Amante, the north Boulder coffeehouse that doubles as a rider's hang.

"Where we headed today?" one silver-haired gent asks.

"Up to NCAR is what I heard," his friend answers. NCAR is the National Center for Atmospheric Research, one of the many federal research institutes that keep Boulder flush with scientific talent.

By 6:20 the joint is packed with bankers, lawyers, startup CFOs, and venture capitalists. There are so many riders that they have to split into three groups: threshold, tempo, and endurance.

This is networking Boulder-style. The town's business culture sees outdoor activity as a productivity aid, not a shirker's lark. A lunch-hour run or ride is encouraged (and many offices have showers and bike rooms). "At my last company, I had a powder-day clause," Newman told me. "Unless we were 24 hours from a major deadline, if there was more than six inches of fresh snow in the mountains, you could skip work and go skiing." Part of the Techstars boot camp often involves a weekly 7 a.m. hike with each company's board of directors. Bicycle meetings are common. "It breaks down the awkwardness," Newman said. "And you're riding together for more than an hour, so inevitably you get to talking about more personal stuff — families, values, philosophy. You just wouldn't do that in an office."

Boulder exercise is social exercise. The tone-setter is the BolderBoulder, the annual Memorial Day 10K that turns the entire town into a jogging party. More than 50,000 people — almost half of Boulder's population — run, jog, juggle, walk, and roll the 10K. Long before Americans raced Tough Mudders, color races, and rock & roll marathons, the BolderBoulder put the fun into the 6.2-mile run.

In this town, exercise isn't a chore — it's a reward.

"It's not perfect here, you know."

I heard that a lot. The comment usually came near conversation's end, and it invariably touched on Boulder's lack of economic and ethnic diversity. How ever white and wealthy you think this town is, it's even whiter and wealthier. You're four times more likely to encounter an African-American in Lincoln, Nebraska, than you are in Boulder. The zoning laws that preserve the town's human scale and open space also prevent most housing development. The fit, outdoor-loving, creative class is migrating to Boulder and squeezing out the working class, the dirtbag climbers, the Zen philosophers, and the ancient hippies nursing cappuccinos at the Trident Café. The homes that were once group rentals for marathoners now get snapped up in all-cash bids by ad execs or tech geeks and their $5,000 Colnago road bikes. According to Zillow, the median home price shot up from $490,000 in 2013 to $696,000 in 2015, and has soared more than 15 percent in the past year alone. With every listing that closes, Boulder gets a little fitter, whiter, and wealthier. This town once welcomed weirdos. Now it welcomes winners.

"It's a very driven culture," a local entrepreneur named Taro Smith told me. "There's no shortage of high-caliber, type A personalities, for good or bad."

The lack of diversity extends beyond race and economic status. Boulder's body-type norms are so extreme that those who don't conform can feel uncomfortable and isolated. Ohio native Kathleen Chaballa went to CU for grad school. She was healthy but not svelte. "I went from being average size for Ohio to being the fattest person in the room," she recalled. "The culture shock was intense."

Chaballa wondered if it was all in her head, until a heavyset friend came to visit. "There are no fat people in this town," her friend observed. "I feel like everyone's staring at me. This is a cool place, but I couldn't live here. I don't know how you do it." Ultimately she couldn't. Chaballa moved to Denver. "There are people of all shapes and sizes here," she told me. "It's a relief."

Here's the thing about Boulderites, though. Even the most comically fit, creative, and successful among them tend not to be assholes. "It's still a small town in a lot of ways," said Nicole Glaros, chief product officer at Techstars. "People look out for each other. If you're a bad actor, you won't get far."

Take Smith. The 43-year-old entrepreneur personifies the kind of person who now thrives in Boulder: one who notices the sparks thrown off by the town's subcultures and captures them to tender new business ideas. Raised in California, Smith came here in the early 1990s to attend college and ski, not necessarily in that order. After graduating, he hung around and co-founded a medical rehab facility. A few years later, in 2005, he and a college buddy, Brandon Dwight, opened Boulder Cycle Sport. Both had been competitive riders in their twenties. "Just what Boulder needed, another bike shop, right?" Dwight said when I later dropped by the store. "But we thought we could make it work." They did, based on their notion of creating community. "Cycling advocacy, group rides, junior cycling, sponsoring a professional cyclocross team — that was how it grew," Smith said.

Boulder is not for everyone. There's a piece of art on Smith's desk. It was a gift from his friend Paul Budnitz, the designer and entrepreneur behind the craft bikemaker Budnitz Bicycles, the designer toy company Kidrobot, and the social network Ello. Budnitz, too, once lived in Boulder. He lasted about two years. "I loved the beauty and a lot of the people," he told me. "But, honestly, I got inundated with the tech culture, people with a lot of entitlement and too much money. It got to be a drag. I felt like I was living someone else's fantasy of a perfect world, but it wasn't mine."

Budnitz ended up in Burlington, Vermont. "There are sophisticated people here doing interesting things," he said, "but there's not so much class division. There's a sense of community."

On my last morning in town, I rose early and did a butt-kicking hike up Mount Sanitas before grubbing huevos rancheros at Caffè Solé in south Boulder. Sitting next to me was a quite fit elderly couple chatting about their African dance class. Two cycling dudes behind me talked about an upcoming century. Across the room I stole a glance at a young climber, his battered backpack parked next to a cheap cup of drip. Scruffy hair, hadn't shaved in a few: classic dirtbag. He was engrossed in a book. I narrowed my eyes to parse the title: Think and Grow Rich. And I thought, "If he wants to stay in Boulder, he'll have to."